Herbert Aptheker, Jewish Marxist and Race-Baiter Par Excellence

Posted by Socrates in "civil rights", 'Black Lives Matter', 'human rights', Blacks in America, communism, Cultural Marxism, Herbert Aptheker, Marxism, Marxism and equality, Marxism as anti-White, New Left, Old Left, race, race baloney, slavery, Socrates, Soviet Union, Victor Perlo at 9:24 am |  Permanent Link

Permanent Link

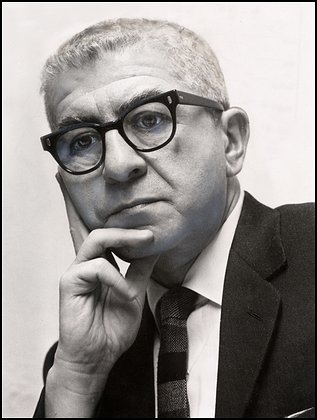

(Above: Herbert Aptheker [1915-2003], a well-known Jewish author and activist, circa 1965. He was famous for being a tireless defender of the Soviet Union, no matter how much blood was being spilled by Stalin).

Of all the Jewish Marxists I’ve mentioned here, somehow I’ve barely mentioned Aptheker — a major oversight to be sure.

Lots of Marxists wrote books, but none wrote as many as Aptheker. If Victor Perlo was the economist of the U.S. Communist Party, then Aptheker was its historian.

Aptheker was probably the foremost communist intellectual during the Cold War. He was a one-man, race-baiting machine who had a foot in both the Old Left and the New Left. He wrote mainly on the topics of Black slavery and Black history, e.g., the huge, 7-volume “A Documentary History of the Negro People in the United States” (1951) [1]. Aptheker has been called “one of the founding scholars” of Black history. It’s logical to say that Aptheker was, with his many books, one of the pioneers of civil-rights studies in America.

Like most Marxists, Aptheker knew that, in order to bring a White country to its knees, you must first divide it into manageable pieces. How? Either economically (via the use of traditional Marxism) or culturally (via the use of Cultural Marxism). Aptheker’s specialty was the latter: divide America by race and sex; pit Blacks against Whites and men against women.

.

[1] “Aptheker long emphasized W. E. B. Du Bois’ social science scholarship and lifelong struggle for African Americans to achieve equality. In his work as a historian, he compiled a documentary history of African Americans in the United States, a monumental collection which he started publishing in 1951. It eventually resulted in seven volumes of primary documents, a tremendous resource for African-American studies.” — Wikipedia