|

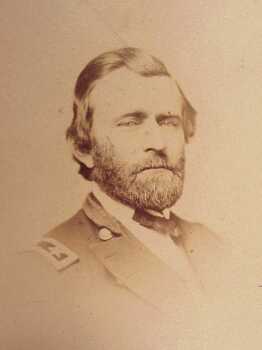

Ulysses Grant has never

been obvious material for a biography because he behaved too well.

Writing about his virtues can quickly turn into homilies about how

decent and inspiring a gentleman he truly was. Some care to

concentrate their energies into proving he was a butcher, a drunkard

or a racist. Let's examine the third charge, specifically that U.S.

Grant was an anti-Semite.

Those who claim he was

anti-Jewish have ready ammunition, which Grant provided with his own

hands. It is his infamous "General Orders Number 11," written in

Oxford, Mississippi, on December 17, 1862. This document essentially

excluded Jews from his department and its racist content has earned

him justifiable censure ever since. The offensive portion of the

order was in the initial paragraph: "The Jews, as a class, violating

every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department,

and also Department orders, are hereby expelled from the

Department." The actual order was signed by the General's chief of

staff, John Rawlins, and zealous supporters of Grant sometimes use

this to absolve their man from blame. Unfortunately, this doesn't

wash. Whether Grant's signature was on the order or not, he was

responsible for both the prevailing sentiment and the order

itself.

Authors favorable to

Grant have bent over backwards in placing the blame on someone

else's shoulders. Even Lloyd Lewis, one of the most capable and

talented of Grant's biographers fell into this trap. He mused, "The

order wasn't like him; (it was) utterly foreign to everything I'd

found out about him." Lewis quoted Grant's father as saying the

order was originally received by Grant from Washington and he merely

passed it along as an official order under his own name. Jesse Grant

figures prominently in the entire quagmire. He maintained at the

time that his son's orders "were issued on express instructions from

Washington," though these supposed orders have never been unearthed,

despite punctilious record keeping by both Grant's staff and

officials in the capitol. John Rawlins echoed Jesse Grant's

sentiments, though he also was vague in his protests and offered no

concrete proof that "Washington" was behind the racist

edict.

The

order is utterly unlike Grant, and he was obviously a man at

the end of his tether when he wrote it. Some of this is due to his

forced inactivity in the Western theatre for 6 months, some is due

to his power struggle with the insubordinate and crass McClernand,

but most of it was due to his father. Grant's relationship with

Jesse Grant is a fascinating psychological contradiction, and there

is little doubt the elder Grant drove his son to fits of despair.

Grant desperately wanted his father's approval, but the cantankerous

old man was so dissimilar from his son that intimacy between them

was impossible. Jesse disliked the General's wife, openly played

favorites among the four Grant children and was an indiscreet

braggart. Grant, normally an impossibly even tempered and gentle

soul, was uncharacteristically harsh to his father in his

correspondence. He frequently rebuked him, though the scoldings did

no good. His father's behavior exasperated and embarrassed him, but

it did not change.

Jesse Grant was an

exceptional businessman, something else that separated father and

son, since the younger Grant was pathetically inept in money

matters. In late 1862, Jesse formed a partnership with a firm called

Mack and Brothers, and it just so happened the Macks were Jewish.

Jesse was keen on going south, gobbling up loads of cheap cotton and

selling it for massive profits in the north. This was not an

uncommon practice and was a lucrative undertaking. In late 1862,

Grant's military control extended into West Tennessee and northern

Mississippi and he was in a position to assist his father's business

schemes. The problem was, Grant wanted no part of profiting through

cotton so long as the war raged, and regarded money making during

wartime as odious. His only concern, as he frequently stated, was

"to put down the Rebellion." When Jesse and the Macks arrived in

Mississippi in late 1862, they wanted permits to buy cotton and ship

huge cratefuls north. Physically and emotionally drained, Grant

lashed out at his father (and the Macks) and issued an unenforceable

decree. He got rid of his father and his business partners, but at

great personal cost to himself.

Even before General

Orders 11, Grant had occasionally expressed anti-Semitic sentiments

in his correspondence. In November, he had written to General

Hurlbut in Jackson, "The Israelites especially should be kept out."

The next day he wrote General Webster a dispatch which stated, "Give

orders to all the conductors on the road that no Jews are to be

permitted to travel on the railroad south from any point... they are

such an intolerable nuisance that the department must be purged of

them." This communication is equally, if not more offensive

than General Orders No. 11.

Grant's decree earned him

official censure in Washington and in two weeks, he received orders

demanding that he revoke it. General Halleck, who was jealous of

Grant's rising fame and military acumen, wrote: "The President has

no objection to your expelling traitors and Jew peddlers, which, I

suppose, was the object of your order; but, as it is in terms

proscribed an entire religious class, some of whom are fighting in

our ranks, the President deemed it necessary to revoke it." Grant

rescinded the offensive decree the following day. Curiously,

newspapers made scant comment at the time, and the issue gained

notoriety only after Grant's death. The General himself remained

strangely mute on this embarrassing and negative event, except to

say meekly, "The order was made and sent out without any

reflection."

In

later years, Grant loyalists scurried to make excuses for the

unseemly event. Simon Wolf, in a 1918 book of reminiscences, claimed

Grant had told him he had "nothing whatever to do" with General

Orders 11, that it was issued by one of his staff officers

(presumably Rawlins) and that he had never vindicated himself

because it wasn't his style. If the incident is true, the fact that

Wolf waited 55 years to tell it cast doubts on its veracity. During

the Presidential campaign in 1868, Wolf had a two hour meeting with

Grant and specifically asked him about the charges of anti-Semitism.

"I know General Grant and his motives," he wrote at the time, "and

assert unhesitatingly that he never intended to insult any

honorable Jew, that he never thought of their religion... the

order never harmed anyone, not even in thought... He is fully aware

of the noble deeds performed by thousands of Jewish privates, and

hundreds of Jewish officers during the late war."

Jewish politicians made a

minor issue of Grant's anti-Semitism during the '68 campaign, but

all those who met and conversed with him were unanimous that he was

not anti-Semitic and they were mystified by this single lapse of

judgment. It did not reflect the inner man. Never again did Grant

make the slightest anti-Semitic remark and in fact, invited Jews to

the White House and entertained them socially. General Orders No.

11, while certainly obnoxious, does not prove anti-Semitism, but

poor judgment.

Sources used: The Papers of Ulysses S.

Grant, Volume 7, pages 50-56, (1979, edited by John Y. Simon),

American Jewry and the Civil War ( 1951, Bertram Korn),

The Papers of U.S. Grant, Volume 19, pages 18-22, (1995,

edited by John Y. Simon). See also

Jews in

the Civil War

.

Ulysses S.

Grant Homepage |

|