|

The Visitor

by Roald Dahl

6 January 2005

Not long ago, a large wooden case was deposited at the door of my house by the railway delivery service. It was an unusually strong and well-constructed object, and made of some kind of dark-red hardwood, not unlike mahogany. I lifted it with great difficulty onto a table and examined it carefully. The stencilling on one side said that it had been shipped from Hifa by the m/v Wavereley Star, but I could find no sender's name or address. I tried to think of somebody living in Haifa or thereabouts who might be wanting to send me a magnificent present. I could think of no one. I walked slowly to the toolshed, still pondering the matter deeply, and returned with a hammer and screwdriver. Then I began gently to prise open the top of the case.

Behold it was filled with books! Extraordinary books! One by one, I lifted them all out (not yet looking inside any of them) and stacked them in three tall piles on the table. There were twenty-eight volumes altogether, and very beautiful they were indeed. Each of them was identically and superbly bound in rich green morocco, with the initials O.H.C. and a Roman numeral (1 to XXVIII) tooled in gold upon the spine.

I took up the nearest volume, number XVI, and opened it. The unlined white pages were filled with a neat small handwriting in black ink. On the title page was written "1934." Nothing else. I took up another volume, number XXI. It contained more manuscript in the same handwriting, but on the title page it said "1939." I put it down and pulled out Vol. 1, hoping to find a preface of some kind there, or perhaps the author's name. Instead, I found an envelope inside the cover. The envelope was addressed to me. I took out the letter it contained and glanced quickly at the signature. Oswald Hendryks Cornelius, it said.

It was Uncle Oswald!

No member of the family had heard from Uncle Oswald for over thirty years. This letter was dated March 10, 1964, and until its arrival, we could only assume that he still existed. Nothing was really known about him except that he lived in France, that he travelled a great deal, that he was a wealthy batchelor with unsavoury but glamorous habits who steadfastly refused to have anything to do with his own relatives. The rest was all rumour and hearsay, but the rumours were so splendid and the hearsay so exotic that Oswald had long since become a shining hero and a legend to us all.

"My dear boy," the letter began, "I believe that you and your three sisters are my closest surviving blood relations. You are therefore my rightful heirs, and because I have made no will, all that I leave behind me when I die will be yours. Alas, I have nothing to leave. I used to have quite a lot, and the fact that I recently disposed of it all in my own way is none of your business. As consolation, though, I am sending you my private diaries. These, I think, ought to remain in the family. They cover all the best years of my life, and it will do you no harm to read them. But if you show them around or lend them out to strangers, you do so at your own great peril. If you publish them, then that, I should imagine, would be the end of both you and your publisher simultaneously. For you must understand that thousands of the heroines whom I mention in the diaries are stillo only half dead, and if you were foolish enough to splash their lilywhite reputations with scarlet print, they would have your head on a salver in two seconds flat, and probably roast it in the oven for good measure. So you'd better be careful. I only met you once. That was years ago, in 1921, when you family was living in that large ugly house in South Wales. I was your big uncle and you were a very small boy, about five years old. I don't suppose you remember the young Norwegian nursemaid you had then. A remarkably clean, well-built girl she was, and exquisitely shaped even in her uniform with its ridiculous starchy white shield concealing her lovely bosom. The afternoon I was there, she was taking you for a walk in the woods to pick bluebells, and I asked if I might come along. And when we got well into the middle of the woods, I told you I'd give you a bar of chocolate if you could find your own way home. You were a sensible child. Farewell -- Oswald Hendryks Cornelius."

The sudden arrival of the diaries caused much excitement in the family, and there was a rush to read them. We were not disappointed. It was quite astonishing stuff -- hilarious, witty, exciting, and often quite touching as well. The man's vitality was unbelievable. He was always on the move, from city to city, from country to country, from woman to woman, and in between the women, he would be searching for spiders in Kashmir or tracking down a blue porcelain vase in Nanking. But the women always came first. Whever he went, he left an endless trail of females in his wake, females ruffled and ravished beyond words, but purring like cats.

Twenty-eight volumes with exactly three hundred pages to each volume take a deal of reading, and there are precious few writers who could hold an audience over a distance like that. But Oswald did it. The narrative never seemed to lose its flavour, the pace seldom slackened, and almost without exception, every single entry, whether it was long or short, and whatever the subject, became a marvellous little individual story that was complete in itself. And at the end of it all, when the last page of the last volume had been read, one was left with the rather breathless feeling that this might just possibly be one of the major autobiographical works of our time.

If it were regarded solely as a chronicle of a man's amorous adventures, then without a doubt there was nothing to touch it. Casanova's Memoirs read like a parish magazine in comparison, and the famous lover himself, beside Oswald, appears positively undersexed.

There was soical dynamite on every page; Oswald was right about that. But he was surely wrong in thinking that the explosions would all come from the women. What about their husbands, the humiliated cock-sparrows, the cuckolds? The cuckold, when aroused, is a very fierce bird indeed, and there would be thousands upon thousands of them rising up out of the bushes if The Cornelius Diaries, unabridged, saw the light of day while they were still alive. Publication, therefore, was right out of the question.

A pity, this. Such a pity, in fact, that I thought something ought to be done about it. So I sat down and reread the diaries from beginning to end in the hope that I might discover at least one complete passage which could be printed and published without involving both the publisher and myself in serious litigation. To my joy, I found no less than six. I showed them to a lawyer. He said he thought they might be "safe," but he wouldn't guarantee it. One of them -- The Sinai Desert Episode -- seemed "safer" than the other five, he added.

So I have decided to start with that one and to offer it for publication right away, at the end of this short preface. If it is accepted and all goes well, then perhaps I shall release one or two more.

The Sinai entry is from the last volume of all, Vol. XXVIII, and is dated August 24, 1946. In point of fact, it is the very last entry of the last volume of all, the last thing Oswald ever wrote, and we have no record of where he went or what he did after that date. One can only guess. You shall have the entry verbatim in a moment, but first of all, and so that you may more easily understand some of the things Oswald says and does in his story, let me try to tell you a little about the man himself. Out of the mass of confession and opinion contained in those twenty-eight volumes, there emerges a fairly clear picture of his character.

At the time of the Sinai episode, Oswald Hendryks Cornelius was fifty-one years old, and he had, of course, never been married. "I am afraid," he was in the habit of saying, "that I have been blessed, or should I call it burdened, with an uncommonly fastidious nature."

In some ways, this was true, but in others, and especially insofar as marriage was concerned, the statement was the exact opposite of the truth.

The real reason Oswald had refused to get married was simply that he had never in his life been able to confine his attentions to one particular woman for longer than the time it took to conquer her. When that was done, he lost interest and looked around for another victim.

A normal man would hardly consider this a valid reason for remaining single but Oswald was not a normal man. He was not even a normally polygamous man. He was, to be honest, such a wanton and incorrigible philanderer that no bride on earth would have put up with him for more than a few days, let alone for the duration of a honeymoon -- although heaven knows there were enough who would have been willing to give it a try.

He was a tall, narrow person with a fragile and faintly aesthetic air. His voice was soft, his manner was courteous, and at first sight he seemed more like a gentleman-in-waiting to the Queen than a celebrated rapscallion. He never discussed his amorous affairs with other men, and a stranger, though he might sit and talk with him all evening, would be unable to observe the slightest sign of deceit in Oswald's clear blue eyes. He was, in fact, precisely the sort of man that an anxious father would be likely to choose to escort his daughter safely home.

But sit Oswald beside a woman, a woman who interested him, and instantaneously his eyes would change, and as he looked at her, a small dangerous spark would begin dancing slowly in the very centre of each pupil; and then he would set about her with his conversation, talking to her rapidly and cleverly and almost certainly more wittily than anyone else had ever done before. This was a gift he had, a most singular talent, and when he put his mind to it, he could make his words coil themselves around and around until they held her in some sort of a mild hypnotic spell.

But it wasn't only his fine talk and the look in his eyes that fascinated the women. It was also his nose. (In Vol. XIV, Oswald includes, with obvious relish, a note written to him by a certain lady in which she describes such things as this in great detail.) It appears that when Oswald was aroused, something odd would begin to happen around the edges of his nostrils, a tightening of the rims, a visible flaring which enlarged the nostril holes and revealed whole areas of the bright red skin inside. This created a queer, wild, animalistic impression, and although it may not sound particularly attractive when described on paper, its effect upon the ladies was electric.

Almost without exception, women were drawn toward Oswald. In the first place, he was a man who refused to be owned at any price, and this automaticaly made him desirable. Add to this the unusual combination of a first-rate intellect, an abundance of charm, and a reputation for excessive promiscuity, and you have a potent recipe.

Then again, and forgetting for a moment the disreputable and licentious angle, it should be noted that there were a number of other surprisign facets to Oswald's character that in themselves made him a rather intriguing person. There was, for example, very little that he did not know about nineteenth-century Italian opera, and he had written a curious little manual upon the three composers Donizetti, Verdi, and Ponchielli. In it, he listed by name all the important mistresses that these men had had during their lives, and he went on to examine, in a most seroius vein, the relationship between creative passion and carnal passion, and the influence of the one upon the other, particularly as it affected the works of these composers.

Chinese porcelain was another of Oswald's interests, and he was acknowledged as something of an international authority in this field. The blue vases of the Tchin-Hoa period were his special love, and he had a small but exquisite collection of these pieces.

He also collected spiders and walking-sticks.

His collection of spiders, or more accurately, his collection of Arachnida, because it included scorpions and pedipalps, was possibly as comprehensive as any outside a museum, and his knowledge of the hundreds of genera and species was impressive. He maintained, incidentally (and probably correctly), that spiders' silk was superior in quality to the ordinary stuff spun by silkworms, and he never wore a tie that was made of any other material. He possessed about forty of these ties altogether, and in order to acquire them in the first place, and in order to be able to add two new ties a year to his wardrobe, he had to keep thousands and thousands of Arana and Epeira diademata (the common English garden spiders) in an old conservatory in the garden of his country house outside Paris, where they bred and multiplied at approximately the same rate as they ate one another. From them, he collected the raw thread himself -- no one else would enter that ghastly glasshouse -- and sent it to Avignon, where it was reeled and thrown and scoured and dyed and made into cloth. From Avignon, the cloth was delivered directly to Sulka, who were enchanged by the whole business, and only too glad to fashion ties out of such a rare and wonderful material.

"But you can't really like spiders?" the women visitors would say to Oswald as he displayed his collection.

"Oh, but I adore them," he would answer. "Especially the females. They remind me so much of certain human females that I know. They remind me of my very

favorite human females."

"What nonsense, darling."

"Nonsense? I think not."

"It's rather insulting."

"On the contrary, my dear, it is the greatest compliment I could pay. Did you not know, for instance, that the female spider is so savage in her love-making that the male is very lucky indeed if he escapes with his life at the end of it all. Only if he is exceedingly agile adn marvelously ingenious will he get away in one piece."

"Now, Oswald!"

"And the crab spider, my beloved, the teeny-weeny little crab spider is so dangerously passionate that her lover has to tie her down with intricate loops and knots of his own thread before he dares to embrace her..."

"Oh, Stop it, Oswald, this minute!" the women would cry, their eyes shining.

Oswald's collection of walking-sticks was something else again. Every one of them had belonged either to a distinguished or a disgusting person, and he kept them all in his Paris apartment, where they were displayed in two long racks standing against the walls of the passage (or should one call it the highway?) which led from the living-room to the bedroom. Each stick had its own little ivory label above it, saying Sibelius, Milton, King Farouk, Dickens, Robespierre, Puccini, Oscar Wilde, Franklin Roosevelt, Goebbels, Queen Victoria, Toulouse-Lautrec, Hindenburg, Tolstoy, Laval, Sarah Bernhardt, Goethe, Vorshiloff, Cezanne, Tojo...There must have been over a hundred of them in all, some very beautiful, some very plain, some with gold or silver tops, and some with curly handles.

"Take down Tolstoy," Oswald would say to a pretty visitor. "Go on, take it down...that's right...and now...now rub your own palm gently over the knob that has been worn to a shine by the great man himself. Is it not rather wonderful, the mere contact of your skin with that spot?"

"It is, rather, isn't it."

"And now take Goebbels and do the same thing. Do it properly, though. Allow your palm to fold tightly over the handle...good...and now...now lean your weight on it, lean hard, exactly as the little deformed doctor used to do...there...that's it...now stay like that for a minute or so and then tell me if you do not feel a thin finger of ice creeping all the way up your arm and into your chest."

"It's terrifying!"

"Of course it is. Some people pass out completely. They keel right over."

Nobody ever found it dull to be in Oswald's company, and perhaps that, more than anything else, was the reason for his success.

We come now to the Sinai episode. Oswald, during that month, had been amusing himself motoring at a fairly leisurely pace down from Khartoum to Cairo. His car was a superlative pre-war Lagonda which had been carefully stored in Switzerland during the war years, and as you can imagine, it was fitted with every kind of gadget under the sun. On the day before Sinai (August 23, 1946), he was in Cairo, staying at Shepheard's Hotel, and that evening, after a series of impudent manoeuvres, he had succeeded in getting hold of a Moorish lady of supposedly aristocratic descent, called Isabella. Isabella happened to be the jealously guarded mistress of none other than a certain notorious and dyspeptic Royal Personage (there was still a monarchy in Egypt then). This was a typically Oswaldian move.

But there was more to come. At midnight, he drove the lady out to Giza and persuaded her to climb with him in the moonlight right to the very top of the great pyramid of Cheops.

"...There can be no safer place," he wrote in the diary, "nor a more romantic one, than the apex of a pyramid on a warm night when the moon is full. The passions are stirred not only by the magnificent view but also by the curious sensation of power that surges within the body whenever one surveys the world from a great height. And as for safety -- this pyramid is exactly 481 feet high, which is 115 feet higher than the dome of St. Paul's Cathedral, and from the summit one can observe all the approaches with the greatest of ease. No other boudoir on earth can offer this facility. None has so many emergency exits, either, so that if some sinister figure should happen to come clambering up in pursuit on one side of the pyramid, one has only to slip calmly and quietly down the other..."

As it happened, Oswald had a very narrow squeak indeed that night. Somehow, the palace must have got word of the little affair, for Oswald from his lofty moonlit pinnacle, suddenly observed three sinister figures, not one closing in on three different sides, and starting to climb. But luckily for him, there is a fourth side to the great pyramid of cheops, and by the time those Arab thugs had reached the top, the two lovers were already at the bottom and getting into the car.

The entry for August 24th takes up the story at exactly this point. It is reproduced here word for word and comma for comma as Oswald wrote it. Nothing has been altered or added or taken away:

August 24, 1946

"He'll chop off Isabella's head if he catch her now," Isabella said.

"Rubbish," I answered, but I reckoned she was probably right.

"He'll chop off Oswald's head, too," she said.

"Not mine, dear lady. I shall be a long way away from here when daylight comes. I'm headed straight up the Nile for Luxor immediately."

We were driving quickly away from the pyramids now. It was about two thirty a.m.

"To Luxor?" she said.

"Yes."

"And Isabella is going with you."

"No," I said.

"Yes," she said.

"It is against my principles to travel with a lady," I said.

I could see some lights ahead of us. They came from teh Mena House Hotel, a place where tourists stay out in the desert, not far from the pyramids. I drove fairly close to the hotel and stopped the car.

"I'm going to drop you here," I said. "We had a fine time."

"So you won't take Isabella to Luxor?"

"I'm afraid not," I said. "Come on, hop it."

She started to get out of the car, then she paused with one foot on the road, and suddenly she wung round and poured out upon me a torrent of language so filthy yet so fluent that I had heard nothing like it from the lips of a lady since...well, since 1931, in Marrakesh, when the greedy old Duchess of Glasgow put her hand into a chocolate box and got nipped by a scorpion I happened to have place there for safe-keeping (Vol. XIII, June 5th, 1931).

"You are disgusting," I said.

Isabella leapt out and slammed the door so hard the whole car jumped on its wheels. i drove off very fast. Thank heaven I was rid of her. I cannot abide bad manners in a pretty girl.

As I drove, I kept one eye on the mirror, but as yet no car seemed to be following me. When I came to the outskirts of Cairo, I began threading my way through the side roads, avoiding the centre of the city. I was not particularly worried. The royal watchdogs were unlikely to carry the matter much further. All the same, it would have been follhardy to go back to Shepheard's at this point. It wasn't necessary anyway, because all my baggage, except for a small valise, was with me in my room when I go out of an evening in a foreign city. I like to be mobile.

I had no intention, of course, of going to Luxor. I wanted now to get away from Egypt altogether. I didn't like the country at all. Come to think of it, I never had. The place made me feel uncomfortable in my skin. It was the dirtiness of it all, I think, and the putrid smells. But then let us face it, it really is a rather squalid country; and I have a powerful suspicion, though I hate to say it, that the Egyptians wash themselves less thoroughly than any other people in the world -- with the possible exception of the Mongolians. Certainly they do not wash their crockery to my taste. There was, believe it or not, a long, crusted, coffee-colored lipmark stamped upon the rim of the cup they placed before me at breakfast yesterday. Ugh! It was repulsive! I kept staring at it and wondering whose slobbery lower lip had done the deed.

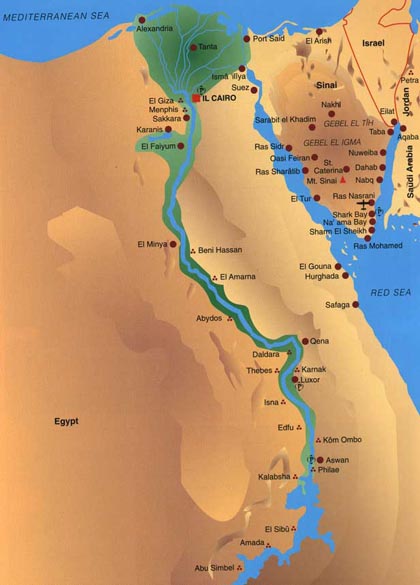

I was driving now through the narrow dirty streets of the eastern suburbs of Cairo. I knew precisely where I was going. I had made up my mind about that before I was even halfway down the pyramid with Isabella. I was going to Jerusalem. It was no distance to speak of, and it was the quickest way out of Egypt. I would proceed as follows:

1. Cairo to Ismailia. About three hours driving. Sing an opera on the way, as usual. Arrive Ismailia 6-7 a.m. Take a room and have a two-hour sleep. Then shower, shave, and breakfast.

2. At 10. a.m., cross over the Suez Canal by the Ismailia bridge and take the desert road across Sinai to the Palestine border. Make a search for scoropions en route in the Sinai Desert. Time, about four hours, arriving Palestine border 2 p.m.

3. From there, continue straight on to Jerusalem via Beersheba, reaching the King David Hotel in time for cocktails and dinner.

It was several years since I had travelled that particular road, but I remembered that the Sinai Desert was an outstanding place for scorpions. I badly wanted another female opisthophthalmus, a large one. My present speciment had the fifth segment of its tail missing, and I was ashamed of it.

It didn't take me long to find the main road to Ismailia, and as soon as I was on it, I settled the Lagonda down to a steady sixty-five miles an hour. The road was narrow, but it had a smooth surface, and there was no traffic. The Delta country lay bleak and dismal around me in the moonlight, the flat treeless fields, the ditches running between, and the black black soil everywhere. It was inexpressibly dreary.

But it didn't worry me. I was no part of it. I was completely isolated in my own luxurious little shell, as snug as a hermit crab and traveling a lot faster. Oh, how I love to be on the move, winging away to new people and new places and leaving the old ones far behind! Nothing in the world exhilarates me more than that. And how I despise the average citizen, who settles himself down upon one tiny spot of land with one asinine woman, to breed and stew and rot in that condition until his life's end. And always with the same woman! I simply cannot believe that any man in his senses would put up with just one female day after day after year after year. Some of them, of course, don't. But millions pretend they do.

I myself have never, absolutely never permitted an intimate relationship to last for more than twelve hours. That is the farthest limit. Even eight hours is stretching it a bit, to my mind. Look at what happened, for example, with Isabella. While we were upon the summit of the pyramid, she was a lady of scintillating parts, as pliant and playful as a puppy, and had I left her there to the mercy of those three Arab thugs, and skipped down on my own, all would have been well. But I foolishly stuck by her and helped her to descend, and as a result, the lovely lady turned into a vulgar screeching trollop, disgusting to behold.

What a world we live in! One gets no thanks these days for being chivalrous.

The Lagonda moved on smoothly through the night. Now for an opera. Which one should it be this time? I was in the mood for Verdi. What about Aida? Of course! It must be Aida -- the Egyptian opera! Most appropriate.

I began to sing. I was in exceptionally good voice tonight. I let myself go. It was delightful; and as I drove through the small town of Bilbeis, I was Aida herself, singing "Numei pieta," the beautiful concluding passage of the first scene."

Half an hour later, at Zagazig, I was Amonasro begging King of Egypt to save the Ethiopian captives with "Ma tu, re, tu signore possente."

Passing through El Abbasa, i was Rhadames, rendering "Fuggiam gli adori nospiti," and now I opened all the windows of the car so that this incomparable love song might reach the ears of the fellaheen snoring in their hovels along the roadside, and perhaps mingle with their dreams.

As I pulled into Ismailia, it was six o'clock in the morning and the sun was already climbing high in milky-blue heaven, but I myself was in the terrible sealed-up dungeon with Aida, singing "O, terra, addio; addio valle di pianti!"

How swiftly the journey had gone. I drove to an hotel. The ataff was just beginning to stir. I stirred them up some more and got the best room available. The sheets and blanket on the bed looked as though they had been slept in by twenty-five unwashed Egyptians on twenty-five consecutive nights, and I tore them off with my own hands (which I scrubbed immediately afterward with antiseptic soap) and replaced thenm with my personal bedding. Then I set my alarm and slept soundly for two hours.

For breakfast I ordered a poached egg on a piece of toast. When the dish arrived -- and I tell you, it makes my stomach curdle just to write about it -- there was a gleaming, curly, jet-black human hair, three inches long, lying diagonally across the yolk of my poached egg. It was too much. I leapt up from the table and rushed out of the dining room. "Addio!" I cried, flinging some money at the cashier as I went by, "addio valle di pianti!" And with that I shook the filthy dust of the hotel from my feet.

Now for the Sinai Desert. What a welcome change that would be. A real desert is one of the least contaminated places on earth., and Sinai was no exception. The road across it was a narrow strip of black tarmac about a hundred and forty miles long, with only a single filling-station and a group of huts at the halfway mark, ata place called B'ir Rawd Salim. Otherwise there was nothing but pure uninhabited desert all the way. It would be very hot at this time of year, and it was essential to carry drinking water in case of a breakdown. I therefore pulled up outside a kind of general store in the main street of Ismailia to get my emergency canister refilled.

I went in and spoke to the proprietor. the man had a nasty case of trachoma. The granulation on the under surfaces of his eyelids was so acute that the lids themselves were raised right up off the eyeballs -- a beastly sight. I asked him if he would sell me a gallon of boiled water. He thought I was made, and madder still when I insisted on following him back into his grimy kitchen to make sure that he did things properly. he filled a kettle with tap-water and placed it on a paraffin stove. The stove had a tiny little smoky yellow flame. the proprietor seemed very proud of the stove and of its performance. he stood admiring it, his head on one side. Then he suggested that I might prefer to go back and wait in the shop. He would bring me the water, he said, when it was ready. I refused to leave. I stood there watching the kettle like a lion, waiting for the water to boil: and while I was doing this, the breakfast scene suddenly started coming back to me in all its horror -- the egg, the yolk, and the hair. Whose hair was it that had lain embedded in the slimy yolk of my egg at breakfast? Undoubtedly it was the cook's hair. And when, pray, had the cook last washed his head? He had probably never washed his head. Very well, then. He was almost certainly verminous. But that in itself would not cause a hair to fall out. What did cause the cook's hair, then, to fall out onto my poached egg this morning as he transferred the egg from the pan to the plate? there is a reason for all things, and in this case the reason was obvious. The cook's scalp was infested with purulent seborrhoeic impetigo. And the hair itself, the long black hair that I might so easily have swallowed had I been less alert, was therefore swarming with millions and millions of living pathogenic cocci whose exact scientific name I have, happily, forgotten.

Can I, you ask, be absolutely sure that the cook had purulent seborrhoeic impetigo? Not absolutely sure -- no. But if he hadn't, then he certainly had ringworm instead. And what did that mean? I knew only too well what it meant. It meant that ten million microsporons had been clinging and clustering around that awful hair waiting to go into my mouth.

I began to feel sick.

"The water boils," the shopkeeper said triumphantly.

"Let it boil," I told him. "Give it eight minutes more. What is it you want me to get -- typhus?"

Personally, I never drink plain water by itself if I can help it, however pure it may be. Plain water has no flavour at all. i take it, of course, as tea or as coffee, but even then I try to arrange for bottled Vichy or Malvern to be used in the preparation. I avoid tap-water. Tap-water is diabolical stuff. Often it is nothing more nor less than reclaimed sewage.

"Soon this water will be boiled away in steam," the proprietor said, grinning at me with green teeth.

I lifted the kettle myself and poured the contents into my canister.

Back in the shop, I bought six oranges, a small watermelon, and a slab of well-wrapped English chocolate. Then I returned to the Lagonda. Now at last I was away.

A few minutes later, I had crossed the sliding bridge that went over the Suez Canal just above Lake Timsah, and ahead of me lay the flat flazing desert and the little tarmac road stretching out before me like a black ribbon all the way to the horizon. I settled the Lagonda down to the usual steady sixty-five miles an hour, and I opened the windows wide. The air that came in was like the breath of an oven. The time was almost noon, and the sun was throwing its heat directly onto the roof of the car. My thermometer inside registered 103 degrees. But as you know, a touch of warmth never bothers me so long as I am sitting still and am wearing suitable clothes -- in this case a pair of cream-coloured linen slacks, a white Aertex shirt, and a spider's silk tie of the loveliest, rich moss-green. I felt perfectly comfortable and at peace with the world.

For a minute or two I played wit the idea of performing another opera en route -- I was in the mood for La Giaconda -- but after singing a few bars of the opening chorus, I began to perspeire slightly; so I rang down the curtain,l and lit a cigarette instead.

I was now driving through some of the finest scorpion country in the world, and I was eager to stop and make a search before I reached the halfway filling-station at B'ir Rawd Salim. I had so far met not a single vehicle nor seen a living creature since leaving Ismailia an hour before. This pleased me. Sinai was authentic desert. I pulled up on the side of the road and switched off the engine. I was thirsty, so I ate an orange. Then I put my white topee on my head, and eased myself slowly out of the car, out of my comfortable hermit-crab shell, and into the sunlight. For a full minute I stood motionless in the middle of the road, blinking at the brilliance of the surroundings.

There was a blazing sun, a vast hot sky, and beneath it all on every side a great pale sea of yellow sand that was not quite of this world. There were mountains now in the distance on the south side of the road, bare, pale, tanagra-couloured mountains faintly glazed with blue and purple, that rose up suddenly out of the desert and faded away in a haze of heat against the sky. The stillness was overpowering. There was not sound at all, no voice of bird or insect anywhere, and it gave me a queer godlike feeling to be standing there alone in the middle of such a splendid, hot, inhuman landscape -- as though I were on another planet altogether, on Jupiter or Mars, or still in some place where never would the grass grow nor the clouds turn red.

I went to the boot of the car and took out my killing-box, my net, and my trowel. Then I stepped off the road into the soft burning sand. I walked slowly for about a hundred yards into the desert, my eyes searching the ground. I was not looking for scorpions but the lairs of scorpions. the scorpion is a cryptozoic and nocturnal creature that hides all through the day either under a stone or in a burrow, according to its type. Only after the sun has gone down does it come out to hunt for food.

The one I wanted, opisthophthalmus, was a burrower, so I wasted no time turning over stones. I searched only for burrows. After ten or fifteen minutes, I had found none; but already the heat was getting to be too much for me, and I decided reluctantly to return to the car. I walked back very slowly, still watching the ground, and I had reached the road and was in the act of stepping onto it when all at once, in the sand, not more than twelve inches from the edge of the tarmac, I caught sight of a scorpion's burrow.

I put the killing-box and the net on the ground beside me. Then, with my little trowel, I began very cautiously to scrape away the sand all around the hole. This was an operation that never failed to excite me. It was like a treasure hunt -- a treasure hunt with just the right amount of danger accompanying it to stir the blood. I could feel my heart beating away in my chest as I probed deeper and deeper into the sand.

And suddenly...there she was!

Oh, my heavens, what a whopper! A gigantic female scorpion, not opisthophthalmus, as I saw immediately, but pandinus, the other large African burrower. And clinging to her back -- this was too good to be true! -- swarming all over her, were one, two, three, four, five...a total of fourteen tiny babies! The mother was six inches long at least! Her children were the size of small revolver bullets. She had seen me now, the first human she had ever seen in her life, and her pincers were wide open, her tail was curled high over her back like a question mark, ready to strike. I took up the net, and slid it swiftly underneath her, and scooped her up. She twisted and squirmed, striking wildly in all directions with the end of her tail. I saw a single large drop of venom fall through the mesh onto the sand. Quickly, I transferred her, together with all the offspring, to the killing-box, and closed the lid. Then I fetched the ether from the car, and poured it through the little gauze hole in the top of the box until the pad inside was well-soaked.

How splendid she would look in my collection! The babies would, of course, fall away from her as they died, but I would stick them on again with glue in more or less their correct positions; and then I would be the proud possessor of a huge female pandinus with her own fourteen offspring on her back! I was extremely pleased. I lifeted the killing-box (I could feel her thrashing about furiously inside) and placed it in the boot, together with the net and trowel. Then I returned to my seat in the car, lit a cigarette, and drove on.

The more contented I am, the slower I drive. I drove quite slowly now, and it must have taken me nearly an hour more to reach B'ir Rawd Salim, the halfway station. It was a most unenticing place. On the left, there was a single gasoline pump and a wooden shack. On the right, there were three more shacks, each about the size of a potting shed. The rest was desert. There was not a soul in sight. The time was twenty minutes before the car was 106 degrees.

What with the nonsense of getting the water boiled before leaving Ismailia, I had forgotten completely to fill up with gasoline before leaving, and my gauge was now registering slightly less than two gallons. I'd cut it rather fine -- but no matter. I pulled in alongside the pump, and waited. Nobody appeared. I pressed the horn button and the four tuned horns on the lagonda shouted their wonderful "Son gia mille e tre!" across the desert. Nobody appeared. I pressed again. "Son gia mille e tre!" sang the horns. Mozart's phrase sounded magnificent in these surroundings. But still nobody appeared. The inhabitants of B'ir Rawd Salim didn't give a damn, it seemed, about my friend Don Giovanni and the one thousand and three women he had deflowered in Spain.

At last, after I had played the horns no less than six times, the door of the hut behind the gasoline pump opened and a tallish man emerged and stood on the threshhold, doing up his buttons with both hands. He took his time over this, and not until he had finished did he glance upu at the Lagonda. I looked back at him through my open window. I saw him take the first step in my direction...he took it very, very slowly...Then he took a second step...

My God! I thought at once. The spirochetes have got him!

He had the slow, wobbly walk, the loose-limbed, high-stepping gait of a man with locomotor ataxia. With each step he took, the front foot was raised high in the air before him and brought down violently to the ground, as though he were stampig on a dangerous insect.

I thought: I had better get out of here. I had better start the motor and get the hell out of here before he reaches me. But I knew I couldn't. I had to have the gasoline. I sat in the car staring at the awful creature as he came stamping laboriously over the sand. He must have had the revolting disease for years and years, otherwise it wouldn't have developed into ataxis. Tabes dorsalis, they call it in professional circles, and pathologically this means that the victim is suffering from degeneration of the posterior columns of the spinal cord. But ah my foes and oh my friends, it is really a lot worse than that; it is a slow and merciless consuming of the actual nerve fibers of the body by syphilitic toxins.

The man -- the Arab, I shall call him -- came right up to the door of my side of the car and peered in through the open window. I leaned away from him, praying that he would not come an inch closer. Without a doubt, he was one of the most blighted humans I had ever seen. His face had the eroded, eaten-away look of an old wood-carving when the worm has been at it, and the sight of it made me wonder how many other diseases the man was suffering from, besides syphilis.

"Salaam," he mumbled.

"Fill up the tank," I told him.

He didn't mnove. He was inspecting the interior of the Lagonda with great interest. A terrible feculent odour came wafting in from his direction.

"Come along!" I said sharply. "I want some gasoline!"

He looked at me and grinned. It was more of a leer than a grin, an insolent mocking leer that seemed to be saying, "I am the king of the gasoline pump at B'ir Rawd Salim! Touch me if you dare!" A fly had settled in the corner of one of his eyes. He made no attempt to brush it away.

"You want gasoline?" he said, taunting me.

I was about to swear at him, but I checked myself just in time, and answered politely, "Yes please, I would be very grateful."

He watched me slyly for a few moments to be sure I wasn't mocking him, then he nodded as though satisfied now with my behavior. He turned away and started slowly toward the rear of the car. I reached into the door-pocket for my bottle of Glenmorangie. I poured myself a stiff one, and sat sipping it. That man's face had been within a yard of my own; his foetid breath had come pouring into the car...and who knows how many billions of airborne viruses might not have come pouring in with it? On such an occasion it is a fine thing to sterilize the mouth and throat with a drop of Highland whisky. The whisky is also a solace. I emptied the glass, and poured myself another. Soon I began to feel less alarmed. I noticed the watermelon lying on the seat beside me. i decided that a slice of it at this moment would be refreshing. I took my knife from its case and cut out a thick section. Then, with the point of the knife, I carefully picked out all the black seeds, using the rest of the melon as a receptacle.

I sat drinking the whisky and eating the melon. Both were delicious.

"Gasoline is done," the dreadful Arab said, appearing at the window. "I check water now, and oil."

I would have preferred him to keep his hands off the Lagonda altogether, but rather than risk an argument, I said nothing. He went clumping off toward the front of the car, and his walk reminded me of a drunken Hitler Stormtrooper doing the goosestep in very slow motion.

Tabes dorsalis, as I live and breathe.

The only other disease to induce that queer high-stepping gait is chronic beriberi. Well -- he probably had that one, too. I cut myself another slice of watermelon, and concentrated for a minute or so on taking out the seeds with the knife. When I looked up again, I saw that the Arab had raised the bonnet of the car on the righthand side, and was bending over the engine. His head and shoulders were out of sight, and so were his hands and arms. What on earth was the man doing? The oil dipstick was on the other side. I rapped on the windshield. He seemed not to hear me. I put my head out of the window and shouted, "Hey! Come out of there!"

Slowly, he straightened up, and as he drew his right arm out of the bowels of the engine, I saw that he was holding in his fingers something that was long and black and curly and very thin.

"Good God!" I thought. "He's found a snake in there!"

He came round to the window, grinning at me and holding the object out for me to see; and only then, as I got a closer look, did I realize that it was not a snake at all -- it was the fan-belt of my Lagonda!

All the awful implications of suddenly being stranded in this outlandish place with this disgusting man came flooding over me as I sat there staring dumbly at my broken fan-belt.

"You can see," the Arab was saying, "it was hanging on by a single thread. A good thing I noticed it."

I took it from him and examined it closely. "You cut it!" I cried.

"Cut it?" he answered softly. "Why should I cut it?"

To be perfectly honest, it was impossible for me to judge whether he had or had not cut it. If he had, then he had also taken the trouble to fray the severed ends with some instrument to make it look like an ordinary break. Even so, my guess was that he had cut it, and if I was right then the implications were more sinister than ever.

"I suppose you know I can't go on without a fan-belt?" I said.

He grinned again, with that awful mutilated mouth, showing ulcerated gums. "If you go now," he said, "you will boil over in three minutes."

"So what do you suggest?"

"I shall get another fan-belt."

"You will?"

"Of course. There is a telephone here, and if you will pay for the call, I will telephone to Ismailia. And if they haven't got one in Ismailia, I will telephone to Cairo. There is no problem."

"No problem!" I shouted, getting out of the car. "And when, pray, do you think the fan-belt is going to arrive in this ghastly place?"

"There is a mail-truck that comes through every morning about ten o'clock. You would have it tomorrow."

The man had all the answers. He never even had to think before replying.

This bastard, I thought, has cut fan-belts before.

I was very alert now, and watching him closely.

"They will not have a fan-belt for a machine of this make in Ismailia," I said. "It would have to come from the agents in Cairo. I will telephone them myself." the fact that there was a telephone gavce me some comfort. The telephone poles had followed the road all the way across the desert, and I could see the two wires leading into the hut from the nearest pole. "I will ask the agents in Cairo to set out immediatley for this place in a special vehicle," I said.

The Arab looked along the road toward Cairo, some two hundred miles away. "Who is going to drive six hours here and six hours back to bring a fan-belt?" he said. "The mail will be just as quick."

"Show me the telephone," I said, starting toward the hut. Then a nasty thought struck me, and I stopped.

How could I possibly use this man's contaminated instrument? The earpiece would have to be pressed against my ear, and the mouthpiece would almost certainly touch my mouth; and I didn't give a damn what the doctors said about the impossibility of catching syphilis from remote contact. A syphilitic mouthpiece was a syphilitic mouthpiece, and you wouldn't catch me putting it anywhere near my lips, thank you very much. I wouldn't even enter his hut.

I stood there in the sizzling heat of the afternoon and looked at the Arab with his ghastly diseased face, and the Arab looked back at me, as cool and unruffled as you please.

"You want the telephone?" he asked.

"No," I said. "Can you read English?"

"Oh, yes."

"Very well. I shall write down for you the name of the agents and the name of the car, and also my own name. They know me there. You will tell them what is wanted. And listen...tell them to dispatch a special car immediately at my expense. I will pay them well. And if they won't do that, tell them they have to get the fan-belt to Ismailia in time to catch the mail-truck. You understand?"

"There is no problem," the Arab said.

So I wrote down what was necessary on a piece of paper and gave it to him. He walked away with that slow, stamping tread toward the hut, and disappeared inside. I closed the bonnet of the car. Then I went back and sat in the driver's seat to think things out.

I poured myself another whisky, and lit a cigarette. There must be some traffic on this road. Somebody would surely come along before nightfall. But would that help me? No, it wouldn't -- unless I were prepared to hitch a ride and leave the lagonda and all my baggage behind to the tender mercies of the Arab. Was I prepared to do that? I didn't know. Probably yes. But if I were forced to stay the night, I would lock myself in the car and try to keep awake as much as possilbe. On no account would I enter the shack where that creature lived. Nor would I touch his food. I had whisky and water, and I had half a watermelon and a slab of chocolate. That was ample.

The heat was pretty bad. The thermometer in the car was still around 104 degrees. It was hotter outside in the sun. I was perspiring freely. My god, what a place to get stranded in! And what a companion!

After about fifteen minutes, the Arab came out of the hut. I watched him all the way to the car.

"I talked to the garage in Cairo," he said, pushing his face through the window. "Fan-belt will arrive tomorrow by mail-truck. Everything arranged."

"Did you ask them about sending it at once?"

"They said impossible," he answered.

"You're sure you aske them?"

He inclined his head ot one side and gave me that sly insolent grin. I turned away and waited for him to go. He stayed where he was. "We have house for visitors," he said. "You can sleep there very nice. My wife will make food, but you will have to pay."

"Who else is here besides you and your wife?"

"Another man," he said. He waved an arm in the direction of the three shacks across the road, and I turned and saw a man standing in the doorway of the middle shack, a short wide man who was dressed in dirty khaki slacks and shirt. He was standing absolutely motionless in the shadow of the doorway, his arms dangling at his sides. He was looking at me.

"Who is he?" I said.

"Saleh."

"What does he do?"

"He helps."

"I will sleep in the car," I said. And it will not be necessary for your wife to prepare food. I have my own." The Arab shrugged and turned away and started back toward the shack where the telephone was. I stayed in the car. What else could I do? It was just after two thirty. In three or four hours' time it would start to get a little cooler. Then I could take a stroll and maybe hunt up a few scorpions. Meanwhile, I had to make the best of things as they were. I reached into the back of the car where I kept my box of books and, without looking, I took out the first one I touched. The box contained thirty or forty of the best books in the world, and all of them could be reread a hundred times and would improve with each reading. It was immaterial which one I got. It turned out to be The Natural History of Selborne. I opened it at random...

". . . We had in this village more than twenty years ago an idiot boy, whom I well remember, who, from a child, showed a strong propensity to bees; they were his food, his amusement, his sole object. And as people of this cast have seldom more than one point in view, so this lad exerted all his few faculties on this one pursuit. In the winter he dosed away his time, within his father's house, by the fireside, in a kind of torpid state, seldom departing from the

chimney-corner; but in the summer he was all alert, and in quest of

his game in the fields, and on sunny banks. Honeybees, humble-

bees, and wasps, were his prey wherever he found them: he had no

apprehensions from their stings, but would seize them nudis

manibus, and at once disarm them of their weapons, and suck their

bodies for the sake of their honey-bags. Sometimes he would fill

his bosom between his shirt and his skin with a number of these

captives; and sometimes would confine them in bottles. He was a

very merops apiaster, or bee-bird; and very injurious to men that

kept bees; for he would slide into their bee-gardens, and, sitting

down before the stools, would rap with his finger on the hives, and

so take the bees as they came out. He has been known to overturn

hives for the sake of honey, of which he was passionately fond.

Where metheglin was making he would linger round the tubs and

vessels, begging a draught of what he called bee-wine. As he ran

about he used to make a humming noise with his lips, resembling

the buzzing of bees. . . ."

I glanced up from the book and looked around me. The motionless man from across the road had disappeared. There was nobody in sight. The silence was eerie, and the stillness, the utter stillness and desolation of the place was profoundly oppressive. I knew i was being watched. I knew that every little move I made, every sip of whisky and every puff of a cigarette, was being carefully noticed. I detest violence and I never carry a weapon. But I could have done with one now. For a while, I toyed with the idea of starting the motor and driving on down the road until the engine boiled over. But how far would I get? Not very far in this heat and without a fan. One mile, perhaps, or two at the most...

No -- to hell with it. I would stay where I was and read my book.

It must have been about an hour later that I noticed a small dark speck moving toward me along the road in the far distance, coming from the Jerusalem direction. I laid aside my book without taking my eyes away from the speck. I watched it growing bigger and bigger. It was travelling at a great speed, at a really amazing speed. I got out of the Lagonda and hurried to the side of the road and stood there, ready to signal the driver to stop.

Closer and closer it came, and when it was about a quarter of a mile away, it began to slow down. Suddenly, I noticed the shape of its radiator. It was a Rolls-Royce! I raised an arm and kept it raised, and the big green car with a man at the wheel pulled in off the road and stopped beside my Lagonda.

I felt absurdly elated. Had it been a Ford or a Morris, I would have been pleased enough, but i would not have been elated. The fact that it was a Rolls -- a Bentley would have done equally well, or an Isotta, or another Lagonda -- was a virtual guarantee that I would receive all the assistance I required; for whether you know it or not, there is a powerful brotherhood existing among people who own very costly automobiles. They respect one another automatically, and the reason they respect one another is simply that wealth respects wealth. In point of fact, there is nobody in the world that a very wealthy person respects more than another very wealthy person, and because of this, they naturally seek each other out wherever they go. Recognition signals of many kinds are used among them. With the female, the wearing of massive jewels is perhaps the most common; but the costly automobile is also much favoured, and is used by both sexes. It is a travelling placard, a public declaration of affluence, and as such, it is also a card of membership to that excellent unofficial society, the Very-Wealthy-People's Union. I am a member myself of long standing, and am delighted to be one. When I meet another member, as I was about to do now, I feel an immediate rapport. I respect him. We speak the same language. He is one of us. I had good reason, therefore, to be elated.

The driver of the Rolls climbed out and came toward me.

"But my dear fellow! You mustn't put a thing like that on the floor!"

"It is touched only by bare feet," I said.

That pleased him. It seemed that he loved carpets almost as much as I loved the blue vases of Tchin-Hoa.

Soon we turned left off the tarred road and onto a hard tony track and headed straight over the desert toward the mountain. "This is my private driveway," Mr. Aziz said. "It is five miles long."

"You are even on the telephone," I said, noticing the poles that branched off the main road to follow his private drive.

And then suddenly a queer thought struck me.

That Arab at the filling-station . . . he also was on the telephone . . .

Might not this, then, explain the fortuitous arrival of Mr. Aziz?

Was it possible that my lonely host had devised a clever method of shanghai-ing travellers off the road in order to provide himself with what he called "civilised company" for dinner? Had he, in fact, given the Arab standing instructions to immobilise the cars of all likely-looking persons one after the other as they came along? "Just cut the fan-belt, Omar. Then phone me up quick. But make sure it's a decent-looking fellow with a good car. Then I'll pop along to see if I think he's worth inviting to the house . . ."

It was ridiculous, of course.

"I think," my companion was saying, "that you are wondering why in the world I should choose to have a house out here in a place like this."

"Well, yes, I am a bit."

"Everyone does," he said.

"Everyone," I said.

"Yes," he said.

Well, well, I thought -- everyone.

"I live here," he said, "because I have a peculiar affinity with the desert. I am drawn to it the same way as a sailor is drawn to the sea. Does that seem so very strange to you?"

"No," I answered, "it doesn't seem strange at all."

He paused and took a pull at his cigarette. Then he said, "That is one reason. But there is another. Are you a family man, Mr. Cornelius?"

"Unfortunately not," I answered cautiously.

"I am," he said. "I have a wife and a daughter. Both of them, in my eyes at any rate, are very beautiful. My daughter is just eighteen. She has been to an excellent boarding-school in England, and she is now . . ." he shrugged . . . "she is now just sitting around and waiting until she is old enough to get married. But this waiting period -- what does one do with a beautiful young girl during that time? I can't let her loose. She is far too desirable for that. When I take her to Beirut, I see the men hanging around her like wolves waiting to pounce. It drives me nearly out of my mind. I know all about men, Mr. Cornelius. I know how they behave. It is true, of course, that I am not the only father who has had this problem. But the others seem somehow able to face it and accept it. They let their daughters go. They just turn them out of the house and look the other way. I cannot do that. I simply cannot bring myself to do it! I refuse to allow her to be mauled by every Achmed, Ali, and Hamil that comes along. And that, you see, is the other reason why I live in the desert -- to protect my lovely child for a few more years from the wild beasts. Did you say that you had no family at all, Mr. Cornelius?"

"I'm afraid that's true."

"Oh." He seemed disappointed. "You mean you've never been married?"

"Well . . . no," I said. "No, I haven't." I waited for the next inevitable question. It came about a minute later.

"Have you never wanted to get married and have children?"

They all asked that one. It was simply another way of saying, "Are you, in that case, homosexual?"

"Once," I said. "Just once."

"What happened?"

"There was only one person ever in my life, Mr. Aziz . . . and after she went . . ." I sighed.

"You mean she died?"

I nodded, too choked up to answer.

"My dear fellow," he said. "Oh, I am so sorry. Forgive me for intruding."

We drove on for while in silence.

"It's amazing," I murmured, "how one loses all interest in matters of the flesh after a thing like that. I suppose it's the shock. One never gets over it."

He nodded sympathetically, swallowing it all.

"So now I just travel around trying to forget. I've been doing it for years . . ."

We had reached the foot of Mount Maghara now and were following the track as it curved around the mountain toward the side that was invisible from the road -- the north side. "As soon as we round the next bend you'll see the house," Mr. Aziz said.

We rounded the bend . . . and there it was! I blinked and stared, and I tell you that for the first few seconds I literally could not believe my eyes. I saw before me a white castle -- I mean it -- a tall, white castle with turrets and towers and little spires all over it, standing like a fairy-tale in the middle of a small splash of green vegetation on the lower slope of the blazing-hot, bare, yellow mountain! It was fantastic! It was straight out of Hans Christian Andersen or Grimm. I had seen plenty of romantic-looking Rhine and Loire valley castles in my time, but never before had I seen anything with such a slender, graceful, fairy-tale quality as this! The greenery, as I observed when we drew closer, was a pretty garden of lawns and date-palms, and there was a high white wall going all the way round to keep out the desert.

"Do you approve?" my host asked, smiling.

"It's fabulous!" I said. "It's like all the fairy-tale castles in the world made into one."

"That's exactly what it is!" he cried. "It's a fairy-tale castle! I built it especially for my daughter, my beautiful Princess."

And the beautiful Princess is imprisoned within its walls by her strict and jealous father, King Abdul Aziz, who refuses to allow her the pleasures of masculine company. But watch out, for here comes Prince Oswald Cornelius to the rescue! Unbeknownst to the King, he is going to ravish the beautiful Princess, and make her very happy.

"You have to admit it's different," Mr. Aziz said.

"It is that."

"It is also nice and private. I sleep very peacefully here. So does the Princess. No unpleasant young men are likely to come climbing in through those windows during the night."

"Quite so," I said.

"It used to be a small oasis," he went on. "I bought it from the government. We have ample water for the house, the swimming-pool, and three acres of garden."

We drove through the main gates, and I must say it was wonderful to come suddenly into a miniature paradise of green lawns and flower-beds and palm-trees. Everything was in perfect order, and water-sprinklers were playing on the lawns. When we stopped at the front door of the house, two servants in spotless gallabiyahs and scarlet tarbooshes ran out immediately, one to each side of the car, to open the doors for us.

Two servants? But would both of them have come out like that unless they'd been expecting two people? I doubted it. More and more, it began to look as though my odd little theory about being shanghaied as a dinner guest was turning out to be correct. It was all very amusing.

My host ushered me in through the front door, and at once I got that lovely shivery feeling that comes over the skin as one walks suddenly out of intense heat into an air-conditioned room. I was standing in the hall. The floor was of green marble. On my right, there was a wide archway leading to a large room, and I received a fleeting impression of cool white walls, fine pictures, and superlative Louis XV furniture. What a place to find oneself in, in the middle of the Sinai Desert!

And now a woman was coming slowly down the stairs. My host had turned away to speak to the servants, and he didn't see her at once, so when she reached the bottom step, the woman paused, and she laid her naked arm like a white anaconda along the rail of the banister, and there she stood, looking at me as though she were Queen Semiramis on the steps of Babylong, and I was a candidate who might or might not be to her taste. Her hair was jet-black, and she had a figure that made me wet my lips.

When Mr. Aziz turned and saw her, he said, "Oh darling, there you are. I've brought you a guest. His car broke down at the filling station -- such rotten luck -- so I asked him to come back and stay the night. Mr. Cornelius . . . my wife."

"How very nice," she said quietly, coming forward.

I took her hand and raised it to my lips. "I am overcome by your kindness, madame," I murmured. There was, upon that hand of hers, a diabolical perfume. It was almost exclusively animal. The subtle, sexy secretions of the sperm-whale, the male musk-deer, and the beaver were all there, pungent and obscene beyond words; they dominated the blend completely, and only faint traces of the clean vegetable oils -- lemon, cajuput, and zeroli -- were allowed to come through. It was superb! And another thing I noticed in the flash of that first moment was this: When I took her hand, she did not, as other women do, let it lie limply across my palm like a fillet of raw fish. Instead, she placed her thumb underneath my hand, with the fingers on top; and thus she was able to -- and I swear she did -- exert a gentle but suggestive pressure upon my hand as I administered the conventional kiss.

"Where is Diana?" asked Mr. Aziz.

"She's out by the pool," the woman said. And turning to me, "Would you like a swim, Mr. Cornelius? You must be roasting after hanging around that awful filling-station."

She had huge velvet eyes, so dark they were almost black, and when she smiled at me, the end of her nose moved upward, distending the nostrils.

There and then, Prince Oswald Cornelius decided that he cared not one whit about the beautiful Princess who was held captive in the castle by the jealous King. He would ravish the Queen instead.

"Well..." I said.

"I'm going to have one," Mr. Aziz said.

"Let's all have one," his wife said. "We'll lend you a pair of trunks."

I asked if I might go up to my room first and get out a clean shirt and clean slacks to put on after the swim, and my hostess said, "Yes, of course," and told one of the servants to show me the way. He took me up two flights of stairs, and we entered a large white bedroom which had in it an exceptionally large double-bed. There was a well-equipped bathroom leading off to one side, with a pale-blue bathtub and a bidet to match. Everywhere, things were scrupulously clean and very much to my liking. While the servant was unpacking my case, I went over to the window and looked out, and I saw the great blazing desert sweeping in like a yellow sea all the way from the horizon until it met the white garden wall just below me, and there, within the wall, I could see the swimming-pool, and beside the pool there was a girl lying on her back in the shade of a big pink parasol. The girl was wearing a white swimming-costume, and she was reading a book. She had long, slim legs and black hair. She was the Princess.

What a set-up, I thought. The white castle, the comfort, the cleanliness, the air-conditioning, the two dazzlingly beautiful females, the watchdog husband, and a whole evening to work in! the situation was so perfectly designed for my entertainment that it would have been impossible to improve upon it. The problems that lay ahead appealed to me very much. A simple, straightforward seducation did not amuse me anymore. There was no artistry in that sort of thing; and I can assure you that had I been able, by waving a magic wand, to make Mr. Abdul Aziz, the jealous watchdog, disappear for the night, I would not have done so. I wanted no pyrrhic victories.

When I left the room, the servant accompanied me. We descended the first flight of stairs, and then, on the landing of the floor below my own, I paused and said casually, "Does the whole family sleep on this floor?"

"Oh, yes," the servant said. "That is the master's room there" -- indicating a door -- "and next to it is Mrs. Aziz. Miss Diana is opposite."

Three separate rooms. All very close together. Virtually impregnable. I tucked the information away in my mind and went on down to the pool. My host and hostess were there before me.

"This is my daughter, Diana," my host said.

The girl in the white swimming-suit stood up and I kissed her hand. "Hello, Mr. Cornelius," she said.

She was using the same heavy animal perfume as her mother -- ambergris, musk, and castor! What a smell it had -- bitchy, brazen, and marvellous! I sniffed at it like a dog. She was, I thought, even more beautiful than the parent, if that were possible. She had the same large velvety eyes, the same black hair, and the same shape of face; but her legs were unquestionably longer, and there was something about her body that gave it a slight edge over the older woman's: it was more sinuous, more snaky, and almost certain to be a good deal more flexible. But the older woman, who was probably thirty-seven and looked no more than twenty-five, had a spark in her eye that the daughter could not possibly match.

Eeny, meeny, miny, mo -- just a little while ago, Prince Oswald had sworn that he would ravish the Queen alone, and to hell with the Princess. But now that he had seen the Princess in the flesh, he did not konw which one to prefer. Both of them, in their different ways, held forth a promise of innumerable delights, the one innocent and eager, the other expert and voracious. The truth of the matter was that he would like to have them both -- the Princess as an hors d'oeuvre, and the Queen as the main dish.

"Help yourself to a pair of trunks in the changing-room, Mr. Cornelius," Mrs. Aziz was saying, so I went into the hut and changed, and when I came out again the three of them were already splashing about in the water. I dived in and joined them. The water was so cold it made me gasp.

"I thought that would surprise you," Mr. Aziz said, laughing. "It's cooled. I keep it at sixty-five degrees. It's more refreshing in this climate."

Later, when the sun began dropping lower in the sky, we all sat around in our wet swimming-clothes while a servant brought us pale, ice-cold martinis, and it was at this point that I began, very slowly, very cautiously, to seduce the two ladies in my own particular fashion. Normally, when I am given a free hand, this is not especially difficult for me to do. The curious little talent that I happen to possess -- the ability to hypnotise a woman with words -- very seldom lets me down. It is not, of course, done only with words. The words themselves, the innocuous, superficial words, are spoken only by the mouth, whereas the real message, the improper and exciting promise, comes from all the limbs and organs of the body, and is transmitted through the eyes. More than that I cannot honestly tell you about how it is done. The point is that it works. It works like cantharides. I believe that I could sit down opposite the Pope's wife, if he had one, and within fifteen minutes, were I to try hard enough, she would be leaning toward me over the table with her lips apart and her eyes glazed with desire. It is a minor talent, not a great one, but I am nonetheless thankful to have had it bestowed upon me, and I have done my best at all times to see that it has not been wasted.

So the four of us, the two wondrous women, the little man, and myself, sat close together in a semi-circle beside the swimming-pool, lounging in deck-chairs and sipping our drinks and feeling the warm six o'clock sunshine upon our skin. I was in good form. I made them laugh a great deal. The story about the greedy old Duchess of Glasgow putting her hand in the chocolate box and getting nipped by one of my scorpions had the daughter falling out of her chair with mirth; and when I described in detail the interior of my spider breeding-house in the garden outside Paris, both ladies began wriggling with revulsion and pleasure.

It was at this stage that I noticed the eyes of Mr. Abdul Aziz resting upon me in a good-humoured, twinkling kind of way. "Well, well," the eyes seemed to be saying, "we are glad to see that you are not quite so disinterested in women as you led us to believe in the car . . . Or is it, perhaps, that these congenial surroundings are helping you to forget that great sorrow of yours at last . . ." Mr. Aziz smiled at me, showing his pure white teeth. It was a friendly smile. I gave him a friendly smile back. What a friendly little fellow he was. he was genuinely delighted to see me paying so much attention to the ladies. So far, then, so good.

I shall skip very quickly over the next few hours, for it was not until after midnight that anything really tremendous happened to me. A few brief notes will suffice to cover the intervening period:

At seven o'clock, we all left the swimming-poll and returned to the house to dress for dinner.

At eight o'clock, we assembled in the big living-room to drink another cocktail. The two ladies were both superbly turned out, and sparkling with jewels. Both of them wore low-cut, sleeveless evening-dresses which had come, without any doubt at all, from some great fashion house in Paris. My hostess was in black, her daughter in pale blue, and the scent of that intoxicating perfume was everywhere about them. What a pair they were! The older woman had that slight forward hunch to her shoulders which one sees only in the most passionate and practised of females; for in the same way as a horsey woman will become bandy-legged from sitting constantly upon a horse, so a woman of great passion will develop a curious roundness of the shoulders from continually embracing men. It is an occupational deformity, and the noblest of them all.

The daughter was not yet old enough to have acquired this singular badge of honor, but with her it was enough for me simply to stand back and observe the shape of her body and to notice the splendid sliding motion of her thighs underneath the tight silk dress as she wandered about the room. She had a line of tiny soft golden hairs growing all the way up the exposed length of her spine, and when I stood behind her it was difficult to resist the temptation of running my knuckles up and down those lovely vertebrae.

At eight thirty, we moved into the dining-room. The dinner that followed was a really magnificent affair, but I shall waste no time here describing food or wine. Throughout the meal I continued to play most delicately and insidiously upon the sensibilities of the women, employing every skill that I possessed; and by the time the dessert arrived, they were melting before my eyes like butter in the sun.

After dinner we returned to the living-room for coffee and brandy, and then, at my host's suggestion, we played a couple of rubbers of bridge.

By the end of the evening, I knew for certain that I had done my work well. The old magic had not let me down. Either of the two ladies, should circumstances permit, was mine for the asking. I was not deluding myself over this. It was a straightforward, obvious fact. It stood out a mile. The face of my hostess was bright with excitement, and whenver she looked at me across the card-table, those huge dark velvety eyes would grow bigger and bigger, and the nostrils would dilate, and the mouth would open slightly to reveal the tip of a moist pink tongue squeezing through between the teeth. It was a marvellously lascivious gesture, and more than once it caused me to trump my own trick. The daughter was less daring but equally direct. Each time her eyes met mine, and that was often enough, she would raise her brows just the tiniest fraction of a centimetre, as though asking a question; then she would make a quick sly little smile, supplying the answer.

"I think it's time we all went to bed," Mr. Aziz said, examining his watch. "It's after eleven. Come along, my dears."

Then a queer thing happened. At once, without a second's hesitation and without another glance in my direction, both ladies rose and made for the door! It was astonishing. It left me stunned. I didn't know what to make of it. It was the quickest thing I'd ever seen. And yet it wasn't as though Mr. Aziz had spoken angrily. His voice, to me at any rate, had sounded as pleasant as ever. But now he was already turning out the lights, indicating clearly that he wished me also to retire. What a blow! I had expected at least to receive a whisper from either the wife or the daughter before we separated for the night, just a quick three or four words telling me where to go and when; but instead, I was left standing like a fool beside the card table while the two ladies glided out of the room.

My host and I followed them up the stairs. On the landing of the first floor, the mother and daughter stood side by side, waiting for me.

"Goodnight, Mr. Cornelius," my hostess said.

"Goodnight, Mr. Cornelius," the daughter said.

"Goodnight, my dear fellow," Mr. Aziz said. "I do hope you have everything you want."

They turned away, and there was nothing for me to do but continue slowly, reluctantly, up the second flight of stairs to my own room. I entered it and closed the door. The heavy brocade curtains had already been drawn by one of the servants, but I parted them and leaned out the window to take a look at the night. The air was still and warm, and a brilliant moon was shining over the desert. Below me, the swimming-pool in the moonlight looked something like an enormous glass mirror lying flat on the lawn, and beside it I could see the four deck-chairs we had been sitting in earlier.

Well, well, I thought. What happens now?

One thing I knew I must not do in this house was to venture out of my room and go prowling around the corridors. That would be suicide. I had learned many years ago that there are three breeds of husband with whom one must never take unnecessary risks -- the Bulgarian, the Greek, and the Syrian. None of them, for some reason, resents you flirting quite openly with his wife, but he will kill you at once if he catches you getting into her bed. Mr. Aziz was a Syrian. A degree of prudence was therefore essential, and if any move were going to be made now, it must be made not by me but by one of hte two women, for only she (or they) would know precisely what was safe and what was dangerous. Yet I had to admit that after witnessing the way in which my host had called them both to heel four minutes ago, there was very little hope of further action in the near future. The trouble was, though, that I had gotten myself so infernally steamed up.

I undressed and took a long cold shower. That helped. Then, because I have never been able to sleep in the moonlight, I made sure that the curtains were tightly drawn together. I got into bed, and for hte next hour or so I lay reading some more of Gilbert White's Natural History of Selborne. That also helped, and at last, somewhere between midnight and one a.m., there came a time when I was able to switch out the light and prepare myself for sleep without altogether too many regrets.

I was just beginning to doze off when I heard some tiny sounds. I recognised them at once. They were sounds that I had heard many times before in my life, and yet they were still, for me, the most thrilling and evocative in the whole world. They consisted of a series of little soft metallic noises, of metal grating gently against metal, and they were made, they were always made, by somebody who was very slowly, very cautiously, turning the handle of one's door from the outside. Instantly, I became wide awake. But I did not move. I simply opened my eyes and stared in the direction of the door; and I can remember wishing at that moment for a gap in the curtain, for just a small thin shaft of moonlight to come in from outside so that I could at least catch a glimpse of the shadow of the lovely form that was about to enter. But the room was as dark as a dungeon.

I did not hear the door open. No hinge squeaked. But suddenly a little gust of air swept through the room and rustled the curtains, and a moment later I heard the soft thud of wood against wood as the door was carefully closed again. Then came the click of the latch as the handle was released.

Next, I heard feet tiptoeing toward me over the carpet.

For one horrible second, it occurred to me that this might just possibly be Mr. Abdul Aziz creeping in upon me with a long knife in his hand, but then all at once a warm extensile body was bending over mine, and a woman's voice was whispering in my ear, "Don't make a sound!"

"My dearest beloved," I said, wondering which one of them it was, "I knew you'd . . . " Instantly her hand came over my mouth.

"Please!" she whispered. "Not another word!"

I didn't argue. My lips had many better things to do than that. So had hers.